Some Brief Reviews

Emilia Pérez (2024)

This is one of the best films of the year, but evidently it’s also one of the most controversial. Written and directed by French filmmaker, Jacques Audiard, it’s about a Mexican cartel boss who hires a lawyer to help him disappear—so he can transition to a woman. It’s also a musical. Karla Sofía Gascón, a Spanish actor who is a trans woman, plays Emilia, and she became the first trans person to be awarded Best Actress at the Cannes Film Festival, in this case alongside her costars, Selena Gomez, Zoe Saldaña and Adriana Paz.

The controversy seems to be that some trans people feel the film doesn’t represent trans people accurately, so it’s “transphobic,” nor does it accurately represent Mexico, so it’s “racist.” Some are comparing it to Crash, a notorious Best Picture winner that was seen as being hopelessly out-of-touch with the world it attempts to depict. That may be true here, too.

Except that Crash was a movie that earnestly attempted to “say something” about racism, and was made with a typical “Hollywood realism” approach, suggesting that we were to take that message seriously. Emilia Pérez, on the other hand, is an over-the-top, high concept, campy, musical fantasia, flooded with emotion, that in no way attempts to be realistic or authentic, except in terms of those very authentic emotions. Audiard originally conceived it as an opera! (It’s also based on a book.)

The movie is not about, nor does it attempt to be about, trans people or Mexico. Rather, it is a movie about personal transformation and whether you can ever escape an evil past, that uses trans and Mexican drug violence to heighten the stakes and the emotions to operatic levels. It’s a wildly, hugely implausible story that we are not meant to take seriously in and of itself. Instead, it presents a serious moral reckoning wrapped up in the color and passion and music of a fable.

Don’t take the haters word for it. They don’t get it. See for yourself.

Battlefield Earth (2000)

This classic goodbad movie is written like a silly comedy in the tone of the BBC’s 1980s Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy series and then played “straight” like it’s a 1980s scifi action movie. Presumably the evil “Psychlos” are a metaphor for the discipline of psychology, sworn enemy of The Church of Scientology, also created by Battlefield Earth scribe, L. Ron Hubbard. Perhaps the cult wanted this seminal text taken seriously? The costumers deserve special praise for creating the indelible Rasta Klingon KISS cover band look.

Blonde (2022)

It's not unusual for my tastes, and my reactions to films, to fall far outside the early consensus. I've gotten used to that. I love goodbad B movies, of course, but that's a different thing. That's an acknowledgement of the badness of a movie while simultaneously proclaiming that it's good for many of the same reasons; it's a camp paradox. Showgirls (1995) is a movie like that, perhaps the greatest example I know of.

But that's not what I'm talking about here. Here we have an example of a movie getting bad reviews from critics and audience members—Rotten Tomatoes is a representative example, with a current 48/39 split for those viewers—that I consider not merely better than that, but a masterpiece. Critics and audiences often get things wrong in the first draft—The Shining (1980), for example, received mixed-to-bad reviews from the New York Times, Variety, Siskel and Ebert's Chicago papers, the Washington Post and the New Yorker, in the person of Pauline Kael. This did not stop it from being a hit—or from going on to be a hugely revered classic, much like many of Kubrick's other initially panned classics, like 2001 or Eyes Wide Shut.

Other directors—notably David Lynch—often make films that are too shocking for viewers to appreciate at first blush. Andrew Dominik's Blonde, like David Lynch's once-hated, now-celebrated Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me (1992), is a brutalizing hallucination of our culture's bottomless misogyny. The two works and the two directors share little else stylistically, but both films also feature a fearless performance for the ages, there in Sheryl Lee's Laura Palmer, here in Ana de Armas's Marilyn Monroe, both inexorably doomed.

This is a pseudo-biography about "Marylin Monroe," not Marilyn Monroe (which is also very much the point). If it has a flaw, it's that the film, based on Joyce Carol Oates’s 2000 novel, makes use of occasionally on-the-nose representations of the character's inner life and the psychology veers toward the dime-store. But ultimately, in my view, these choices make the long, stream-of-consciousness narrative more accessible. It's gorgeously filmed, mixing a variety of looks (it's digital, of course, but frequently mimics various film stocks, aspect ratios and color and grain profiles).

The mix of styles includes many scenes placing de Armas's Marilyn seamlessly into her most famous film roles. In a scene from Some Like It Hot (1959), in which this Monroe has a breakdown while filming with the girlband her character travels with, it looked to me like many of the "girls" were actually played by men, not just Lemmon and Curtis's characters. If so, it's very subtle, but it's an example of some of the hallucinogenic images throughout the film. Another time, a hanging bedsheet on which Marilyn has just had a threesome dissolves seamlessly into Niagara Falls; in another harrowing scene, the open mouths of the men ogling her at a premiere gape wider and more terrifying than in real life.

This most closely resembles a horror movie. Like many horror movies, the director skillfully implicates the audience in the brutality. Some have loudly called Blonde exploitative. I suspect this is because they cannot face their own complicity in our culture's sadistic treatment of women.

Mimic (1997)

(from a four star Letterboxd review)

I was surprised by this movie, which is del Toro's second. It's something like a remake of C.H.U.D., but with cockroaches, which places it in schlock territory; a B-movie at best. And yet, it's like Spielberg's evil twin, an equally talented filmmaker, but with the opposite of Spielberg's sappy worldview, decided to make a crappy horror movie. Like Tarantino making Death Proof, del Toro is so far out of this material's league he ends up making a far better movie than this has any right to be. After all, this is a super-gross story about giant cockroaches that mimic humans.

But the Spielberg comparison is no mere joke. It feels like we're watching a Spielberg movie, but a kind of dark universe one. The camera moves effortlessly to give us just the right way to see each moment, the lighting and design are 1980s Amblin style crossed with del Toro's particular 1990s grunge, like if Seven was lit and designed like Indiana Jones. The Spielbergian themes of family and children are present, but this Evil Steven has no qualms about killing the little ones who stick their noses where they don't belong. Even the music, while creepier than John Williams, mimics his pacing and triumphalism.

It's clearly the work of a devotee of cinema; particularly someone obsessed with monster movies. That's pretty much what del Toro makes each time, is a type of monster movie. Mimic, though it spawned two sequels (without del Toro), did not make back its budget. At a reported $30M, particularly for 1997, this was a high budget horror movie. That's part of why it looks Spielbergian—it's clearly a studio picture with a high production value. This is not always how you want horror to look, to be honest. It's hard to think of many studio horror films (after the 1960s) that can compete with indie horror (e.g., Halloween). Mimic is one that can—its director's vision and sensibility shines through what must have felt like a compromised situation to him on some level. (He evidently had a bad time working for an overbearing Bob Weinstein.)

Would make a great double feature as a second film with any schlocky 70s or 80s underground New York sewer monster movie, C.H.U.D. or another one.

Halloween Kills (2021)

(from a two star Letterboxd review)

When I heard that David Gordon Green and Danny McBride were writing, and Green directing, a series of Halloween sequels, I was surprised, but hopeful. I didn't expect a comedy, but I did think the point would be to have fun. 2018's Halloween is a letdown in that respect; although some of the dialogue is hilarious and the latest retcon entertaining, the enterprise is less fun than it could have been.

Still, it's a far sight better that its sequel, Halloween Kills, released today, in theaters and on the Peacock streaming service, which is how I watched it. Would I have liked it better in a theater? Possibly; though I tend to think I would have been annoyed that I bothered to see it there.

One of the bedrock conceits of the slasher film is that the killer can never really die. This persistent cliche, enabled by Hollywood's bottom-line logic and lack of imagination, has passed through the terrain of scary, to the unbelievable to the ridiculous to the stupid to being a simple expectation of the genre. It has rendered the most famous slashers as kind of shadow superheroes. Just as no superhero can ever really die—for those who want to remind me that Tony Stark/Iron Man has definitively passed on, I suggest just waiting a bit—no slasher can ever be really, actually dead, no matter how many times they die. Once, Jason Voorhees, of Friday the 13th infamy, was actually blown to smithereens, exploding in tiny bloody chunks, but he still persisted (best not to get into it).

So there's no real expectation that, as the marketing for Kills has insisted, "evil dies tonight." We know that's total bullshit, and we would know that even if we didn't know there will be another sequel next year, called Halloween Ends, and we know it won't be true after that movie, either. Still, this doesn't mean we want to be constantly smacked across the face with his inability to be harmed.

This movie wonders what would happen if the people of Haddonfield, led by a motley assembly of Michael Myers survivors, decided that they'd finally had it with this guy and mob up to take him down. This is not a terrible concept, in and of itself, but its execution here feels like it's violating some unspoken rules of the franchise. In a way, that's what makes it interesting—but not as done here.

When Halloween movies work, they rely on Michael terrorizing individuals or a couple of characters at a time, who are almost always completely outmatched. That's the trope and, even if he's shot and stabbed and bashed, we can just suspend our disbelief enough to think maybe, just maybe, he could have survived. Thus the horror.

Here, in two scenes, Michael presents himself to a big group of people—first about a dozen brawny firefighters, later that aforementioned mob—and in both cases he dispatches pretty much everyone on the scene within seconds, regardless of how many of them there are or what weapons they have. Sure, in some cases the victims are hapless in their misuse of their weapons, or Michael is too fast. But in other cases, particularly with the mob, he's shot and stabbed and bashed and shot and stabbed and bashed by a whole bunch of people at the same time, with absolutely no effect whatsoever. He just does the usual thing of getting back up and killing everyone. Then he does the other thing of disappearing from view, even though there are dozens of people around, and showing up a few blocks away to kill again.

I know he's not going to die, yet surviving the massive assault he suffers here has no effect at all. I guess that's the point, that Michael Myers has finally transcended even the petty limitations he previously faced, like the need for a little downtime after being badly wounded. In which case, I have to wonder—why not just throw the playbook away altogether?

I am ready for gonzo Halloween. Rob Zombie's Halloween II (2009) approaches this, but not really in the way I mean. If Michael is essentially a superhero, how about we get crazy with it? There's really no more thinking that he might be killed, no more hope for that. He's a supernatural entity, but he's never been allowed to be that—in spite of everyone from multiple Sam Loomises to endless versions of Laurie Strode (Jamie Lee Curtis has played at least three versions of this character) insisting Michael's "not human" but some kind of "pure evil."

If that's true, can we stop pretending he's also kind of human? Jason, for example, started as a human kid—but even then, he's completely inhuman and only gets more so. All of these movies are dumb (even the original Halloween in some ways, though it's also a masterpiece). I don't see the problem in making them wilder, crazier and even dumber, but fun—and I had initially hoped that's what this writing team would concoct.

Michael Myers can't go to space—but I'm saying he should. I'm saying there should be a Halloween multiverse, in which the insanity of the Halloween "continuity" is the result of parallel dimensions. I'm saying he should team up with Freddy and Jason and Chucky and Pinhead and everybody else to, you know, fight an alien invasion or some shit. Why does this franchise think it's so special? Cause it ain't. Get wild, or give it up, man.

Shiva Baby (2020)

Young writer-director, Emma Seligman, transforms her clever 2018 SXSW student short into a brilliant low-budget feature debut. Not all short-to-feature remakes work nearly this well, as often the essence of the story can’t be easily expanded from its distilled form. Seligman avoids this problem by refocussing on her characters’ relationships and raising the stakes of the titular shiva for her lead. She also pumps up the anxiety of this deeply personal comedy by playing it, at times, more like a thriller or even horror film, with music and shot choices that underscore the often deadpan awkwardness and claustrophobia of family gatherings.

In addition to her loving but overbearing parents and other gossiping Jewish friends and relatives, college senior Danielle finds to her aggravation that both her ex-girlfriend and her “sugar daddy” are at the shiva. His “shiksa” wife and baby are also present. The situation is explosive, but Seligman handles the tension and pressure expertly, by staying close to her lead’s perspective. She doesn’t make too big a thing of Danielle’s bisexuality, or her prostitution (this sugar baby is more than a companion); Jewishness is significantly more important here. Seligman uses the various secret relationships and stereotypical aspects of this reformed Jewish community as sources of comic irony. And she manages to balance these elements with the subtlety, grace and authenticity we would expect from a far more experienced filmmaker.

Halloween: Resurrection (2002)

(from a one star Letterboxd review)

Halloween 8 is atrocious; definitely the worst of all the Halloweens, as of August, 2021. And while you would think that'd be self-evident from the title, and it's beyond pointless to wish for more positive effort in the production of the 8th movie in a horror franchise, still, this is particularly awful. Part of that is criminally bad technical quality in, for example, the shooting and editing. Also the acting, directing, art and craft. Just those things. Oh! almost forgot the writing.

The other part of wishing this was better is that the concept is surprisingly rich, even at the level of its being a weak tea critique of reality TV. It's positively electric with millennial anxiety. The approach to the Halloween story is really smart and interesting and really terribly executed. There are layers of meta distancing and critique embedded in the structure, which incorporates not just reality TV and the early aughts digital video mania but interactivity and spectatorship. But the images are murky and drunkenly edited. Mixing "bad" video with filmed images can work if the video is used for its strengths—its creepy, sinister, cubic darkness, its lack of information, its ability to suggest and shock—think Blair Witch. But the formats have to support each other rather than clash stupidly, in an oily puddle of digital shards.

I can imagine a really strong version of this—maybe not one any studio would green-light. But there are a lot of ideas here. Half a star for the ghost of a great concept.

Half a star for Busta Rhymes, when he "kills" Michael Myers and says (edited awkwardly slowly), "Trick or Treat, motherfucker!"

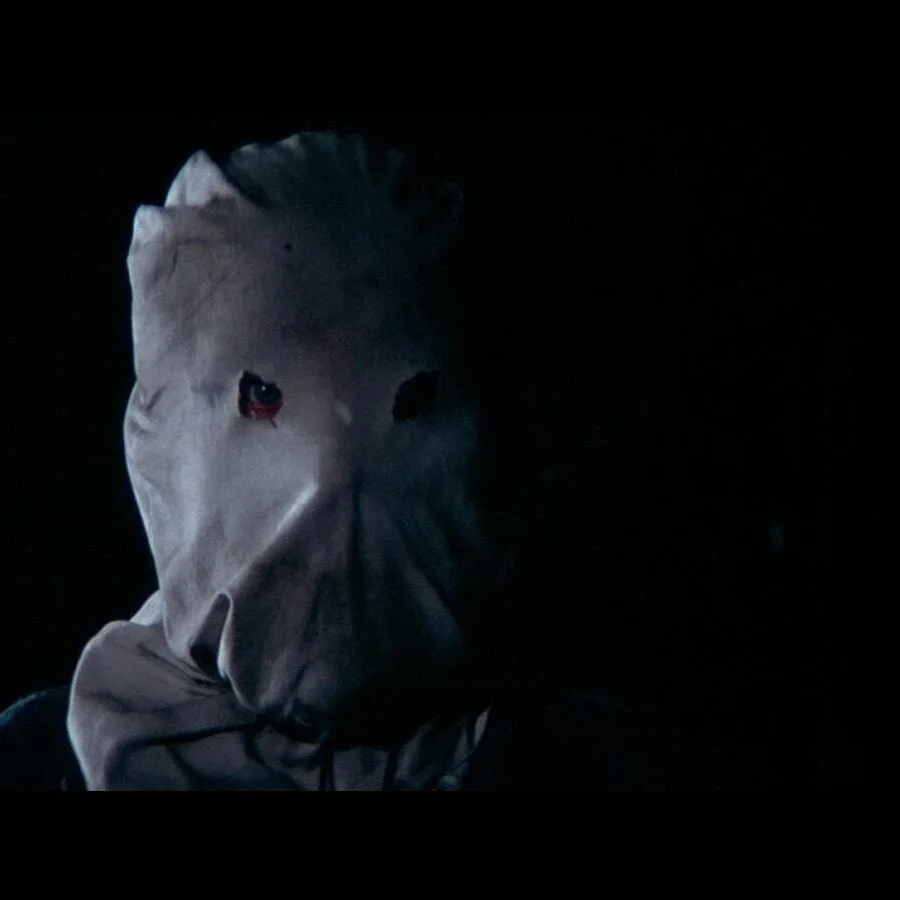

The Town That Dreaded Sundown (1976)

Known as a “proto-slasher,” like Black Christmas or giallo movies, this odd thriller, kind of a horror-drama with comic elements, certainly influenced films that came after it—most famously, Friday the 13th, Part 2, which depicts killer Jason in a bag mask like the Phantom Killer here—but it’s better than most slasher films. Part of this is likely the novelty of a film like this now, after I’ve seen many typical slasher horror films, that employs many of the same tropes but within the context of a different kind of movie.

Part of this movie is a southern cop comedy, reminiscent of the Dukes of Hazzard (or, perhaps, that show’s inspiration, the 1975 film, Moonrunners), in an east Texas setting like Badlands, with Western elements, like Ben Johnson as a Texas Ranger who posses up with local law enforcement to catch the killer. It’s a police procedural that also encompasses teenage sexual shenanigans (though in a relatively chaste manner) and some Apple Dumpling Gang silliness. And, in miniature, the stalking and serial killing tactics of Michael Myers and his slasher progeny.

It’s also a 1940s period piece with a docudrama voiceover that reminds us, every so often, that this is a true story. It’s an entertaining, genuinely unsettling movie that’s a little different from what you expect.

Attack the Block (2011)

When a friend tells me a scifi-comedy-horror movie is “right up my alley,” it’s usually a safe bet. I love genre hybrids, though they can be tough to make, hard to sell and offer many ways to fail. I’m tempted to say they are a type of movie Hollywood often gets spectacularly wrong, while filmmakers a few steps away from Hollywood (and many steps away from the producer’s notes of Hollywood) can often nail it. British comedian Joe Cornish’s Attack the Block is a great example of nailing it. It’s no surprise to find out that Edgar Wright was an Executive Producer on this—his films have a similar sensibility, although this one is darker, to its glory.

I’m a decade late to the party, but this is a cult film that really holds up. It’s an alien invasion story and the creatures are something the film does exceptionally well. This is a low budget movie, relatively speaking, but the creatures, which are so furry and black they can barely be interpreted visually, apart from terrifying glowing slavering mouths with a thousand teeth, work brilliantly. Among a riotous ensemble cast, John Boyega (Finn from Star Wars 7-9) gives a thrilling star turn in his film debut.

This should clearly be counted as a new black horror classic, both as a great action film starring young black men and as a social horror film, like Get Out, that uses the black experience (in Britain, in this case) as part of its subject matter.

Nomadland (2020)

One small silver lining of the pandemic cloud of 2020 is that, in the absence of the usual blockbuster release schedule and marketing machine, a number of smaller films have gotten a bit more attention than they might have in a different year. They would still have showed up in critics lists, for the most part, but I might not have been able to see one of the best films of the year, Chloé Zhou’s Nomadland, for example, on Hulu already. It’s a lightly fictionalized adaptation of the nonfiction book by Jessica Bruder.

Star Frances McDormand and her producing partner optioned the book and brought it to Zhou, whose next film is part of the MCU. This is about as far from that as you can get. It’s quiet, beautiful and shattering; both deeply troubling and apolitically humanist and full of wonder. Among a cast primarily composed of non-actors, McDormand gives them the gift of listening and presence, saying little, simply being, and bringing us, in the true story of older Americans living in their vans, working seasonal jobs (for example, at the Amazon warehouse actually shown in the film, remarkably) and creating community in the southwest desert, the truer story of all of humanity, nomads in an inconceivable cosmos, with but a little time to share.

A.O. Scott, in his Times review, which I found mostly right on the money, admits that he was bothered by the appearance of the veteran actor, David Strathairn, who we notice immediately because he’s the only other recognizable actor in the film. Scott writes, “Our first glimpse of Dave, coming into focus behind a box of can openers at an impromptu swap meet, is close to a spoiler. The vast horizon of Fern’s story suddenly threatens to contract into a plot. He promises — or threatens — that a familiar narrative will overtake both Fern and the movie.” First, Strathairn is wonderful in the film, but Scott isn’t wrong—as soon as he shows up we sense that he will become an important character, possibly a romantic interest. Second, I just happen to think that this plot contrivance—in a movie that largely rejects any plot or drama beyond the workaday struggles of the nomad lifestyle and the joys of friendship—is used beautifully. As McDormand’s Fern gently fends off concerned friends, would-be lovers and a “normal” life of consumption and poverty logic, and grows into a life vastly bigger than herself, so does the film fend off the ordinary, the cliched, the movie logic, that might dictate a different path.

The Rocketeer (1991)

Special effects wizard, Joe Johnston (Star Wars, Raiders of the Lost Ark), began his directing career with Disney’s Honey, I Shrunk the Kids, which he followed up with this comic book adaptation. It bombed, more or less. It’s also one of the best comic book adaptations ever made. I am saying this in 2021. Yes, I know what I’m saying. I would trade more than half of the MCU for a couple more Rocketeer films, if they retained the pure, zippy joy of the original.

Great soundtrack, peak practical effects, deep-bench cast having a ton of fun, awesome design, great period detail and not overly self-serious. It’s thrilling and reasonably scaled (it’s not about gods saving the universe from other gods).

The GoodTimesKid (2005)

An early feature from Azazel Jacobs, son of experimental filmmaker, Ken Jacobs. Emerging at the height of the “mumblecore” period of early 21st century indie filmmaking, this is not a mumblecore film, per se, though it resembles one superficially. This movie, instead, is a more sneakily rigorous minimalist comedy, with only scraps of story actually conveyed through dialogue. Shot around Los Angeles at the same time I was starting film school, it takes me indelibly back to that moment in time and place (it even has a wholly unexpected cameo by one of my professors), and further back to my own twenties.

I say “sneakily” rigorous, because the shooting may seem anything but, with it’s sloppy-seeming lack of focus, high-grain and deadpan, improvisational feel, but it has strong narrative unity and structure and a simplicity that belies its emotional complexity. It’s also an hilarious riff on quarter-life ennui, substituting strong characterization for the usual twee curlicues, that recalls the best moments of bursting life from early Godard and deadpan inertia of early Jarmusch. This charming energy is placed in the service of a melancholy satire on identity that is ultimately quite beautiful and moving.

Lovers Rock (2020)

The second film in Steve McQueen’s extraordinary “Small Axe” series on Amazon Prime is also one of the very best films of 2020. Film Twitter argues about streaming versus theatrical, but what difference does it really make when the movie is this good? There’s a story here—there are a lot of stories here—but they are told in colors, in feelings, in heat, in music, in bodies in motion, more than words. McQueen for long stretches places us in the center of the dance floor and we hear it and we can smell the sweat and the clouds of pot smoke, we feel the floorboards quaking. The camera weaves through the house party, large and small dramas playing out as the night waxes, but in the dance the community is one, loving and living together, becoming the We in Bob Marley’s song: “If you are the big tree/We are the small axe.”

Swamp Thing (1982)

Wes Craven’s Swamp Thing is an example of one that slipped passed me. In fact, I did not see it until yesterday, although I have had a DVD copy for several years. It was a blind buy—junk shop, maybe? that I picked up because it looked like intriguing schlock and cost $5. I was wholly unprepared for the awesomeness of this movie.

One of the great things about Swamp Thing is how it keeps kicking into a higher gear. It starts with a low rumble as we’re introduced to a variety of colorful characters whose relationships and purposes are poorly explained. There are some dubious scientist-types—including terrifying future Twin Peaks dad, Ray Wise, to my delight—and some military types, it’s unclear why, and some cranky outback boss, and then legendarily bodacious scream queen, Adrienne Barbeau as a…what is she supposed to be? She knows things about “sensors,” like the ones placed around the swamp for some reason.

Ray Wise hits on Barbeau immediately, and hard, and takes her for a boat ride in the swamp, on her first day, and even kisses her. So he’s crazy; he and his sister have discovered some kind of substance in the swamp that explodes when dribbled on the ground. Also, it makes things grow like crazy and turns animals into plantimals. The outback boss guy straight up pulls his own face off, like he’s on the Impossible Mission Force, and turns out to be some other guy we’ve never heard of. Then his military thugs start killing everybody, but Barbeau handily kicks their asses and escapes. Ray Wise is less lucky; his body gets dumped in the swamp, never to return, probably. Barbeau meets a young black kid running a gas station; he helps her get away from the bad guys, for a brief moment, and then the thugs toss her in the swamp—but she’s rescued by a slime creature! It’s Ray Wise’s character, transformed into a Swamp Thing!

There are chases, explosions, shoot outs and an actual fucking star wipe, which I think I have never seen used in a real movie, and then the movie becomes a kind of Island of Dr. Moreau’s Beauty and the Beast, with characters taking the special plant goo and transforming into creatures that “reveal their true essence” or some such cockeyed shit. It makes sense that handsy kiss-stealing scientist Ray Wise becomes a slime man, I guess, but who knew he had such a poetic soul, too? Barbeau sees past the slime, into that soul and falls in love—I guess? And some gloriously ridiculous-looking beasties battle to the death.

Obviously, I LOVED it.

Prince of Tides (1991)

This is a Hollywood movie—but I think you have to judge movies on their own merits. It has the inescapable flaws of a mainstream production—it's far too incident-rich, the plotting is somewhat schizophrenic, it's got schmaltz, abetted by the music. But it also delivers something we practically never see in theatrical movies any more—a serious middle-aged adult story, a meaningful melodrama, with moving performances and complex characters.

But, Barbra! An amazing person when you think about it. This is a movie about, among other things, a couple of 50 year olds having a serious affair, without being about aging at all. It's hard to imagine a critically and commercially successful studio movie today even being about this, let alone starring an around 50 year old woman who also PRODUCED AND DIRECTED. In fact, I'm struggling to think of any similar example from all of American film history. (Ida Lupino is the only name that comes to mind.)

The degree to which Streisand asserts her voice, her sexuality and her star power here might be unprecedented. Crazily, even thirty years later. I stand in great admiration of this accomplishment on her part. A true badass.

Never Rarely Sometimes Always (2020)

Rightly called one of the best films of the year (although it’s a really unusual, drought year for culture) this small film makes itself much greater than the sum of its parts in its effect on the viewer. It’s not a character study. It’s a study of a system, through the actions of a teenage girl and her cousin. She is largely closed off to us, in spite of the extraordinary intimacy of the shooting (in the mode of the Dardennes), and we learn some things about why this would be. But she is every girl in conservative rust-belt America trying to exercise her Constitutional right to an abortion; this is the larger point of the film.

This is handled without preaching, without speechifying, without contrived drama or catharsis; instead, with a searing rage just barely concealed and a commitment to simple, procedural realism. It is a nakedly infuriating film. It made me so angry, I wanted to donate immediately to Planned Parenthood, the unnamed heroes of the story. I know people who might be able to watch this movie and still want to criminalize abortion, but I’m not sure how they could justify themselves afterward.

By dealing less with explicitly expressed emotions, writer/director Eliza Hittman opens up our empathy as we reach for this girl, to help her, or hold her, or lift her up. Our rage is in part at ourselves for our categorical failure to protect her. There is no stridency in this film’s argument; there doesn’t need to be. The injustices are too plain.

(Disclosure: I know some of the people who made this movie. Whether that disposes me to be more, or less, critical, is a question of some, perhaps idle, interest. Sometimes when our friends and acquaintances find success, whereas most former film students never make a commercial film, it’s irksome. It’s just human nature, I suppose. It does not describe how I feel, but I know some people who do seem irked.)

Deep Red (1975)

I very begrudgingly enjoyed this film today. I’m not sure I’ve seen it before, although I’ve had the DVD for more than 20 years. It was sort of gifted to me when my best friend OD’d 20 years ago this fall. Hadn’t thought of the fact of that anniversary until now. Would have been a couple months ago or so.

That’s not why the bregrudgement, however. I saw it on a list of best horror movies somewhere and realized I had this old DVD. I have to reconcile myself with the fact that I kind of hate giallo. But why on earth, when surely in many ways it both precedes and exceeds the slasher genre, which I often find entertaining? Certainly, giallo is campy in a way that’s similar to slasher horror, even if the specifics are an ocean apart.

Got me musing. It occurred to me that I was deeply irritated by the design elements of this very Italian film, and thought that perhaps the greatest offense is that it was in Italy. It’s proto-slasher horror, but it takes place in these villas the size of Las Vegas casinos. Even the apartments have a kind of plastic opulence, all this very stupid, 70s crap everywhere, but as a fine sparkly layer over these five hundred year old palazzos. I can’t quite explain why this all infuriated me so much, but I realized that American horror—American Gothic, if you will—feels much closer, because it is, to pioneer traumas. The woods, the beasts, the darkness. A cruel, trackless wilderness, whereas most of Western Europe hasn’t been a cruel, trackless wilderness in millennia.

There’s a very different sense of (white people) history in a country that was barely an inch in some king’s pants 400 years ago versus a country whose capital was founded around 750 BCE. As Americans our most profound (and silliest) fears are still about nature’s maw.

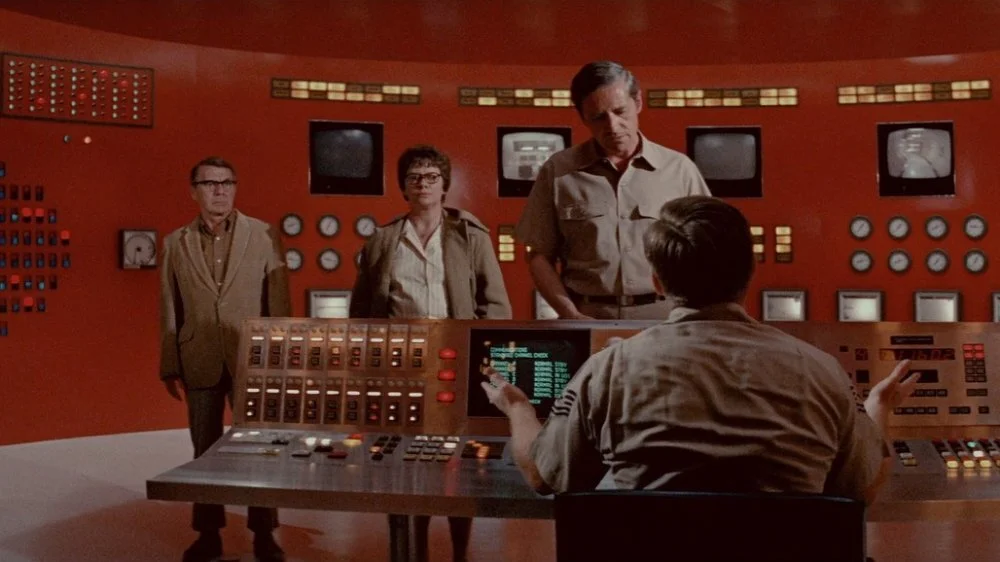

The Andromeda Strain (1971)

Might be the dullest effective thriller ever made—which is part of the point—it takes a pose of super-scientific realism a la 1971, so lots of boring, ugly, old, white mostly male scientists staring at computer screens from 2001: A Space Odyssey, interpreting inscrutable dot matrices with ever greater understated alarm. From the perch of 2020, a pandemic-wracked annus horribilis if ever there was, the "high tech" look of this movie feels hopelessly camp, and it's pretty fascinating.

Which is not to say that this isn't a great film without the camp reading. It's a relic; in part the camp comes from the post-seventies cynicism that finds this view of a techno-utopian, yet functional, US government-in-a-crisis hopelessly naive. This is the Fail Safe to an-as-yet-unmade Dr. Strangelove. While I'd love to see that movie, this movie is an ever tightening screw, with spectacular craft and evident authenticity and care.

On the Rocks (2020)

A disappointedly slight effort from Sofia Coppola. On the other hand, she has never seemed to let that particular criticism bother her, in productive ways in the past. Marie Antoinette is not the grand statement some, perhaps, would have enjoyed. Likewise, On the Rocks still holds some interest. There is a working out of themes and characters that are likely to recur in her filmography—the renowned and obnoxious father and the talented but unsure daughter—in a kind of safe space. I mean, was this dumped on Apple Plus, or is it a signifier of a deliberately light, exploratory piece of work?

Beau Travail (1999)

A haunting, stunningly beautiful masterpiece of longing. Let’s talk about the female gaze, too. And Denis Lavant’s gorgeous ugly mug. He’s like a Neanderthal ballerina. If you watch this movie now (recently a Criterion release), see if you think the kid looks a little Adam Drivery.