They Should Really Just Shake It Off

I’ve talked about copyright issues here before, including in the previous post. Early in this century, there was a surge of interest in copyright issues, in part stemming from the music industry’s panic over Napster. The change from analog to digital across many fields brought both great advantages and disadvantages to many players. Napster and other peer-to-peer music services (along with Apple’s introduction of the iPod in 2001) led to an explosion in music trading by fans that soon disrupted the music industry’s business model and eventually created the new model of streaming music services.

When music fans discovered that some of their favorite artists (such as Metallica) were suing the companies that were making music distribution and sharing so easy and so much fun, a segment of them began learning about copyright law. It was an interesting period in copyright, one of several historical moments when an industry was disrupted and changed irrevocably as a result of technology, and rapid fan adoption of that technology, that did an end run around an industry’s monopolistic practices to the delight of consumers. Steve Jobs and Apple had the insight to see where this was all going, and made billions, whereas the music industry itself frantically tried to use copyright law to squelch these innovations before belatedly admitting defeat and joining the party.

Whether the changes were good or bad for artists, as opposed to record companies and rights-holding entities, has been the subject of much debate over the years. But, while the music industry—and more recently the film and television businesses—were forced to abandon old business models in favor of adopting the new technologies their end users preferred, that conversation about copyright was ultimately one of the big losers of the controversy. Gone today are all of the hopeful new takes on the future of copyright, and the thoughtful and expansive new framings, like Creative Commons, which still exists, are little talked about outside of the narrower channels of discourse these intellectual property arcana have always inhabited.

Instead, the public’s understanding of copyright, which was expanding creatively in the early aughts, has been corralled into the narrow definitions preferred by media corporations and rights clearinghouses. It is in the interests of corporations—like Disney, which has famously lobbied for, and won, extensions to copyright law every time Mickey Mouse was in danger of reverting to the Public Domain—to lock up their copyrighted creations in impenetrable vaults and vigorously attack everyone who seeks to breach those defenses, even, say, daycare centers and elementary schools. Those who hoped to inspire the public to work on legislators to correct some of the egregious cultural problems that emerge from modern IP laws lost resoundingly. We all lost.

Even rich artists lost. Every year there are outrageous examples of artists suing artists over perceived copyright violations. It makes little difference if these lawsuits have any actual relationship to the spirit of the law, or even the letter, because much of copyright and other IP law is caselaw, meaning it’s almost impenetrable to the public and lawyers are left to duke it out. This means settlement after settlement, and terrible precedent after terrible precedent. A couple of examples have recently come to light regarding one of my favorite pop artists, Taylor Swift. Yeah, I admit it. I’m a diehard Swiftie. Check this out.

Pitchfork has been following the cases; here’s a recent example. Here are the two current cases in a nutshell.

The now defunct music group (or the rights holders for) 3LW has sued Taylor Swift over her 2014 mega-hit, Shake It Off, alleging that it violates their copyright established in their 2001 song, Playas Gon’ Play. 3LW claims to have originated the concept that appeared in their lyrics “Playas, they gonna play/And haters, they gonna hate” in that song. Famously, Swift’s song includes the lyrics “'Cause the players gonna play, play, play, play, play/And the haters gonna hate, hate, hate, hate, hate.”

In other words, the 3LW songwriters are claiming to have invented the concept of “playas playing” and “haters hating,” which is patently absurd. Even if they, in fact, had originated this phrasing—which is absurd—they appear to be arguing that they own all subsequent formulations of this extremely well known slang, which is an argument only a copyright lawyer could love. A judge has already ruled against them, but that ruling was overturned (see linked article) in a decision that will send the case to a jury—because the public are well known to be experts in copyright law, obviously.

The only good that can come of this is the sure-to-be-entertaining testimony of experts who will attest to the long-running concept of “player hating,” which Biggie Smalls talked about, before he died in 1997. This is an egregiously frivolous lawsuit.

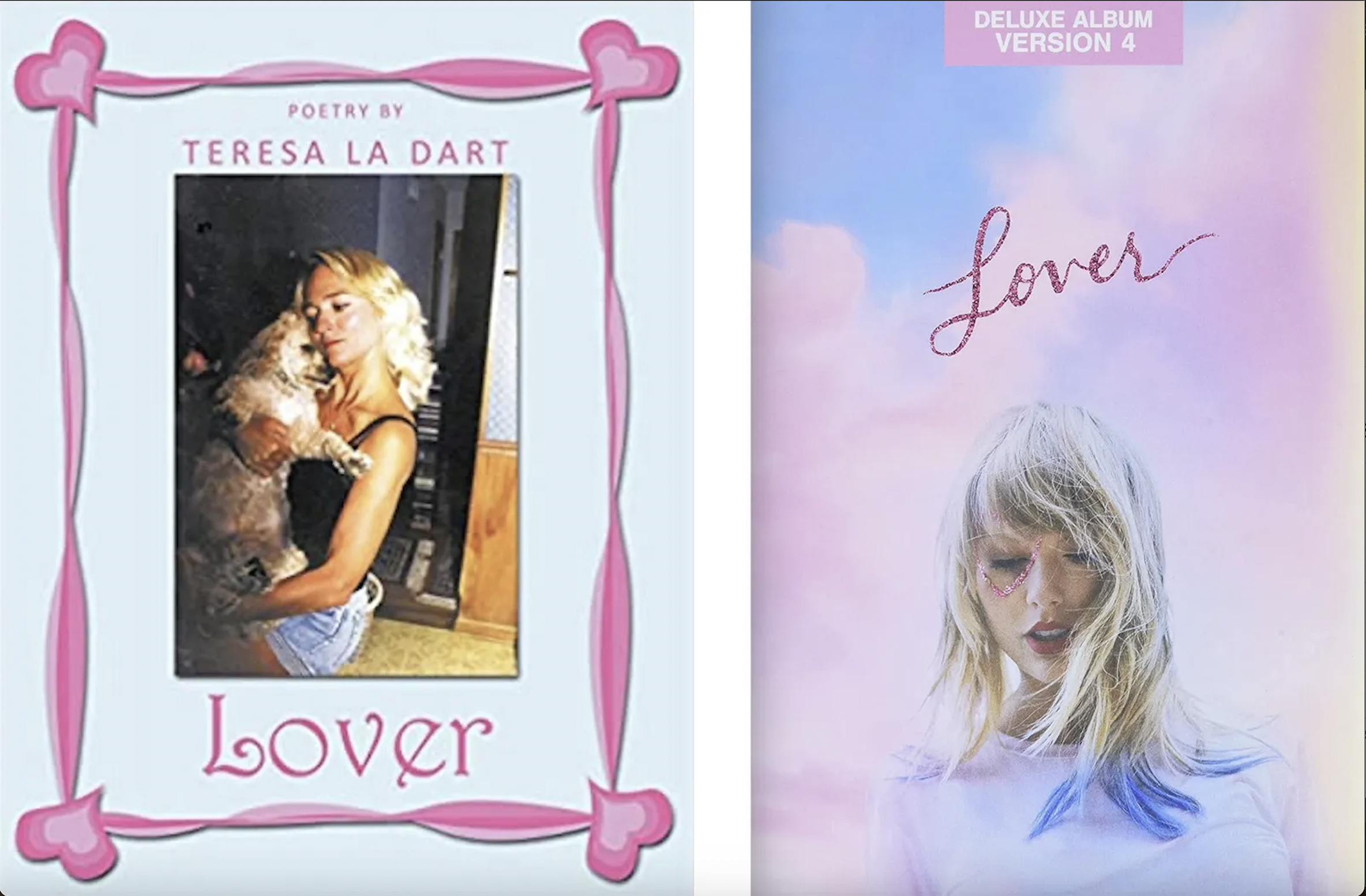

And here’s another one, also referenced in the Pitchfork article. Taylor Swift released a book with a deluxe version of her 2019 album, Lover. She’s being sued by a poet named Teresa La Dart, who released a poetry collection of the same name in 2010, and you can see why when you compare the covers of each book, in this image from a different Pitchfork article:

Pitchfork’s Nina Corcoran wrote, The parts of La Dart’s book that she claims Swift copied include the same title, covers that use “pastel pinks and blues,” and images of the author “photographed in a downward pose.” La Dart alleges that Swift also copied the book’s “format” of “a recollection of past years memorialized in a combination of written and pictorial components” as well as the inner design being made up of “interspersed photographs and writings.

So, the word “lover” used as a title, pastel colors and the posture of a photo subject. And mixing personal memories in text with images. Sure, why the fuck not.

Haters gonna hate.